Beneath the Surface: Unraveling the Anatomy and Biochemistry of Skin in Leather Manufacturing

Estimated Reading time: ~9-10 minutes

Introduction: Where Biology Fuels Leather’s Timeless Craft

Skin structure in leather manufacturing is the cornerstone of success in the industry. In the world of leather manufacturing, success hinges on a profound appreciation for the raw material: animal skin. Far from a simple hide, skin is a marvel of biological engineering, packed with intricate layers, proteins, and amino acids that dictate everything from tanning efficiency to final product durability. Understanding the skin structure in leather manufacturing isn’t just academic—it’s a practical edge for sourcing hides, grading quality, and innovating sustainable processes.

This blog explores the anatomy of skin for leather production, delving into its three primary layers, the biochemistry of key proteins like collagen and elastin, and the role of amino acids in creating resilient leather. We’ll also uncover skin textures and how they influence conversion from raw hide to finished leather. Whether you’re a tanner optimizing processes or a designer seeking superior materials, this knowledge empowers you to elevate quality and sustainability.

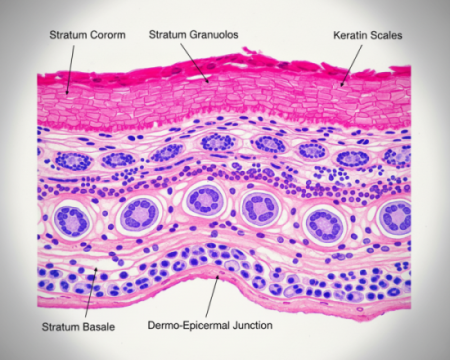

The Epidermis: Nature’s First Line of Defense

The outermost layer of skin, the epidermis, acts as a formidable barrier, protecting the underlying tissues from environmental assaults. Composed primarily of keratinized squamous cells—mostly dead and flattened at the surface—this layer is about 0.05 to 1.5 mm thick, varying by animal species and body region. In leather production, the epidermis is the first to go: it’s meticulously removed during the beamhouse processes like liming and unhairing to prevent contamination and ensure a clean grain surface.

Why Epidermis Matters in Leather Conversion

Without proper removal, residual epidermal cells can lead to uneven dyeing or weakened finishes. The layer’s keratin—a tough, fibrous protein—resists penetration by tanning agents, so stripping it open allows chemicals to reach the true leather core. Texturally, the epidermis contributes to the hide’s initial smoothness or roughness; coarse epidermal scales in bovine hides, for instance, signal potential for full-grain leather if handled delicately.

For deeper insights into beamhouse techniques, check out our upcoming guide on leather tanning processes

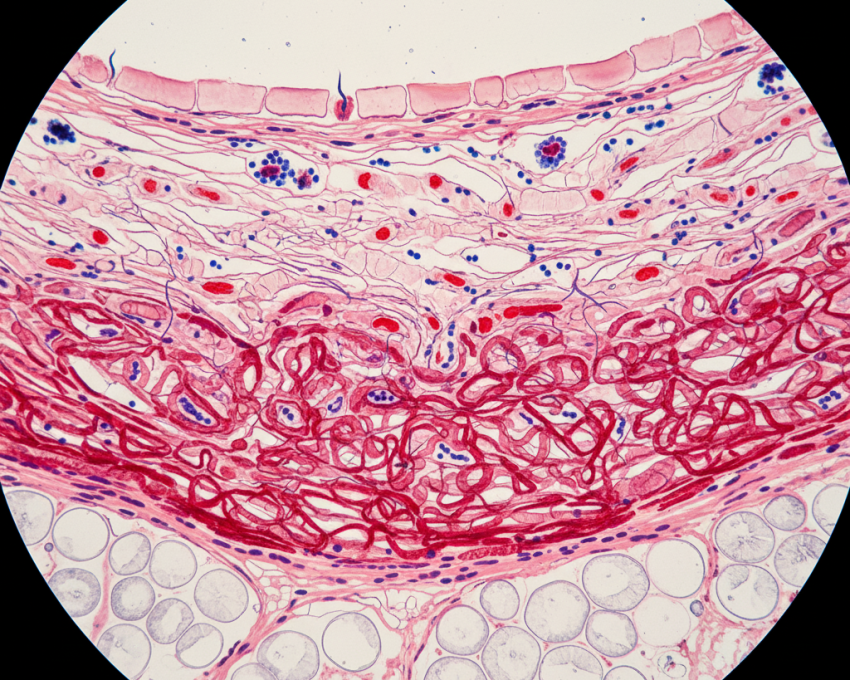

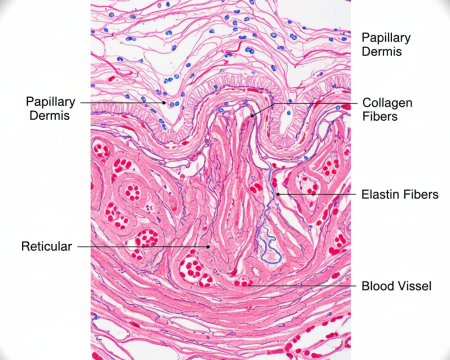

The Dermis: The True Heart of Leather Strength

Nestled beneath the epidermis lies the dermis, the powerhouse layer that forms 90-95% of a hide’s thickness and is the primary source of leather’s coveted properties. Spanning 1-4 mm, it divides into two zones: the papillary dermis (upper, looser weave of fine fibers) and the reticular dermis (lower, dense bundle of coarse collagen). This layered architecture provides tensile strength, elasticity, and vascular support—blood vessels and nerves that, while non-functional post-harvest, influence pre-slaughter hide health.

Textures and Variations in the Dermis

Skin textures in leather manufacturing vary dramatically by animal and anatomy in the dermis. Bovine hides exhibit a tight, wavy grain from compact collagen bundles, ideal for upholstery leather, while ovine (sheep) skins show looser, more porous textures suited for supple garment leathers. Scars or brands disrupt these textures, creating “loose grain” defects detectable via palpation or imaging. Understanding dermal textures aids in grading: A uniform, fine papillary layer predicts smooth full-grain finishes, while reticular density forecasts tear resistance.

From Dermis to Leather: The Conversion Bridge

During tanning, the dermis absorbs vegetable or chrome agents into its open fiber network, cross-linking collagen to prevent putrefaction. This preserves the dermis’s natural elasticity—up to 50% stretch before yield—translating to leather that bends without cracking. Poor dermal integrity from disease or age leads to brittle outcomes, underscoring why healthy, textured dermis is prized.

Explore collagen’s role further in scientific literature like this study on dermal fiber orientation

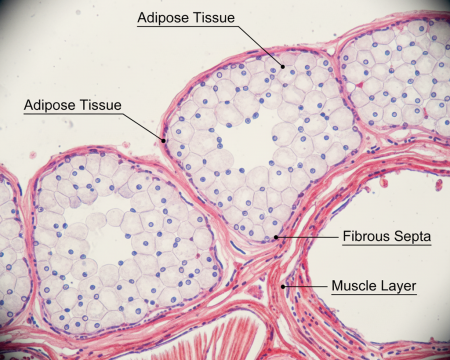

The Hypodermis: Anchoring the Depths

The deepest stratum, the hypodermis (or subcutaneous layer), serves as a fatty cushion, insulating and tethering skin to muscle via loose connective tissue and adipose cells. Thicker in areas like the brisket (up to 10 mm in cattle), it’s laden with collagen and elastin but dominated by lipids—making it less ideal for leather.

Textural Nuances and Processing Implications

Hypodermal textures range from smooth, fatty sheens in young animals to fibrous, veiny marbling in mature ones. This layer’s variability affects fleshing efficiency: Excess fat causes slippage during mechanical removal, while adherent fibers can tear the reticular dermis, downgrading hides. In sustainable practices, trimmed hypodermis is repurposed for gelatin or biofuels, minimizing waste.

Leather Conversion: Trimming for Purity

Post-fleshing, the hypodermis is excised to yield “blue” wet hides focused on the dermis. Retaining traces enhances split leather’s bulk but risks oil staining in top-grain products. Thus, precise hypodermal removal ensures clean conversion, preserving the dermis’s biochemical purity for tanning.

Biochemistry Deep Dive: Proteins, Amino Acids, and Leather’s Molecular Magic

At the molecular level, the dermis’s biochemistry—dominated by proteins and amino acids—orchestrates leather’s transformation. Over 70% of dermal dry weight is collagen, a right-handed triple helix of three polypeptide chains, synthesized by fibroblasts. Supporting players include elastin (for snap-back resilience) and minor globulins.

Spotlight on Key Proteins

|

Protein |

Role in Skin |

Impact on Leather Conversion |

|---|---|---|

|

Collagen |

Tensile scaffold; 300 nm fibrils |

Cross-links during tanning for rot-proof durability; 80% of final leather mass |

|

Elastin |

Elastic recoil; amorphous networks |

Degraded in processing but aids initial flexibility; loss causes stiffness |

|

Keratin |

Epidermal armor (minimal in dermis) |

Fully removed; residues hinder dye uptake |

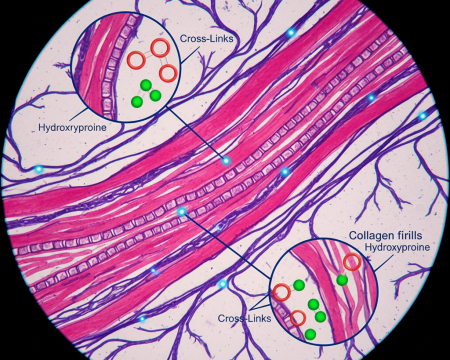

Collagen in leather’s sequence—repeating Gly-X-Y triplets (X often proline, Y hydroxyproline)—enables tight packing, with glycine’s small size (~33% abundance) allowing helical twists.

Amino Acids: The Building Blocks of Resilience

Beyond glycine, proline (10-15%) and hydroxyproline (10%) stabilize helices via hydrogen bonds, while alanine (~8%) and glutamic acid (~7%) add charge balance for fiber alignment. Arginine contributes to cross-linking sites, vital for chrome tanning’s covalent bonds. These amino acids’ ratios predict tannage: High proline hides tan faster, yielding supple leathers; imbalances from poor nutrition cause weak fibers.

Textural Ties to Biochemistry

Dermal textures reflect amino acid distribution—dense reticular zones boast more hydroxyproline for rigidity, while papillary looseness favors elastin-rich elasticity. In conversion, enzymes like proteases target specific peptide bonds, “opening” the matrix for uniform agent penetration, reducing energy use by 20-30% in eco-tanning.

This biochemical lens revolutionizes quality control: Spectroscopic analysis of amino profiles flags defects pre-tanning. For advanced reading, reference this review on collagen biochemistry

How Skin Structure Guides the Path to Premium Leather

Synthesizing layers, textures, and biochemistry reveals a roadmap for converting skin to leather. Healthy epidermal removal exposes a textured dermis primed for biochemical reactions—collagen cross-links form during tanning, elastin degrades controllably, and amino acids dictate finish. Textural mapping via AI imaging now predicts yields, cutting waste by 15%. This holistic view fosters innovation: Bio-engineered collagens mimic natural structures for vegan alternatives, bridging biology and craftsmanship.

Conclusion: Empowering Leather’s Future Through Skin Science

The anatomy and biochemistry of skin isn’t mere trivia—it’s the blueprint for transforming hides into heirloom-quality leather. From the epidermis’s discard to the dermis’s dominance and hypodermis’s trim, every layer and molecule influences efficiency, texture, and sustainability. As you source or process, let this knowledge sharpen your edge: Grade for dermal density, innovate with amino-targeted tannins, and design with biochemical intent.

Stay tuned for our next post on leather tanning mastery, where we’ll apply these insights to real-world production. What’s your biggest challenge in hide processing? Share in the comments!