Biomechanics of the Walking Foot: Mastering Dynamics, Stress Paths, and Optimal Shoe Design

Estimated Reading Time: ~12 minutes

Introduction

This post is a continuation of our series on foot health, building directly on the insights from our previous blog, “Mastering Foot Dynamics, Support, and Balance: The Ultimate Guide for Professional Shoe Fitting Success.” In the intricate dance of human locomotion, the biomechanics of the walking foot stands as a testament to evolutionary ingenuity. Our ability to stride upright—known as orthograde locomotion—is not just a hallmark of Homo sapiens but a symphony of muscular coordination, structural precision, and dynamic balance.

As we delve deeper into walking dynamics, we’ll uncover the core principles, trace the weight stress path through the foot, and contrast it with the amplified demands of the running foot. From heel strikes that propel us forward to the cushioning needs that safeguard our joints, understanding these mechanics is key to selecting footwear that supports—not hinders—our natural gait. Whether you’re a daily walker, avid runner, or shoe fitter, these insights reveal why half of our 650 muscles activate with every step, turning simple ambulation into a profound act of biomechanical harmony.

Core Principles of Walking Dynamics

Walking is far more than a casual stroll—it’s a masterful balancing act of forward propulsion and instantaneous support. Humans uniquely navigate this orthograde gait, upright on two feet, distinguishing us from other species through strides that demand tremendous coordination. Biomechanics, the application of mechanical principles to living organisms, illuminates this process: our body repeatedly “falls forward” only to catch itself, engaging roughly half of our 650 muscles per step. This isn’t mere efficiency; it’s a survival mechanism honed over millennia, where every motion underscores the foot’s role as the body’s foundational fulcrum.

The walking foot transforms under load, distinct from its static or shod resting state. At rest, it’s a stable platform; in motion, it becomes a dynamic lever, adapting shape and proportions to distribute forces. This “third” functional foot—compressed and flexed inside the shoe—highlights why shoe fit must prioritize dynamics over static measurements. Precision fitting here prevents the imbalances that lead to discomfort or injury, ensuring the foot’s sectional design (stable tarsus for support, springy metatarsus for propulsion, grippy phalanges for traction) operates in unison.

Pro Tip: Measure the foot under load (standing and mid-stride if possible) using a dynamic fitting system. Static length alone misleads—focus on volume, arch engagement, and toe splay during motion

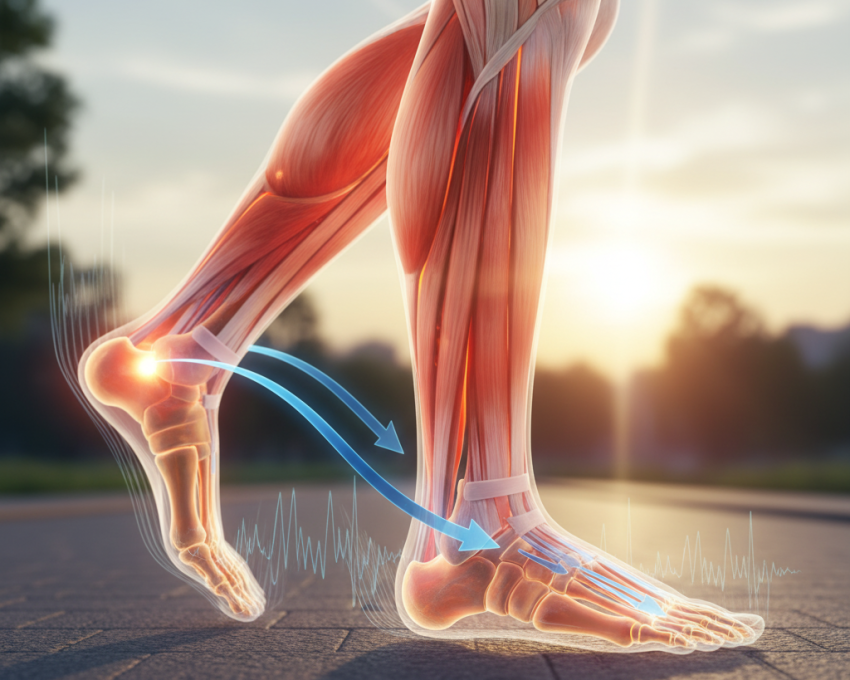

Weight Stress Path Through the Foot

The journey of weight through the foot unfolds in a precise sequence, minimizing trauma while maximizing efficiency:

- Heel Strike: Impact begins at the heel, absorbing initial ground reaction forces.

- Outer Midfoot Transfer: Weight shifts laterally to the outer border of the midfoot for stability.

- Central Midfoot Pivot: An abrupt medial shift centers the load, engaging the arch for support.

- Ball Propulsion: Thrust forward onto the metatarsal heads (ball of the foot) launches the next stride.

This path isn’t random—it’s orchestrated by ligaments, tendons, and muscles to dampen shocks and propel motion. Disruptions, like ill-fitting shoes, can reroute stresses, leading to pronation issues or fatigue.

Pro Tip: Use pressure mapping insoles during fitting to visualize real-time stress paths. Adjust shoe width or add metatarsal pads if weight skips the midfoot or overloads the forefoot.

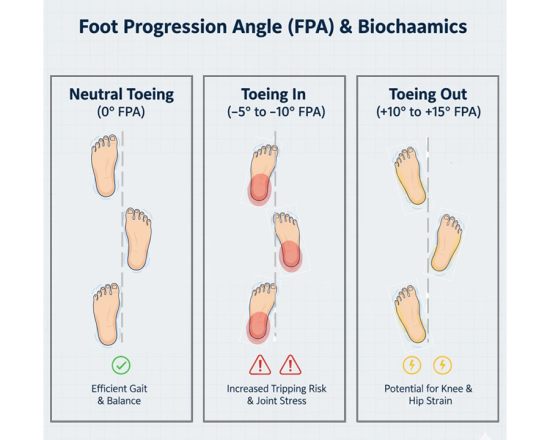

Foot Stances

Foot stances refer to the positioning and orientation of the feet during standing or movement, which directly affects balance, weight distribution, and propulsion in walking. In biomechanics, stance is analyzed in phases: initial contact (heel strike), mid-stance (full foot support), and terminal stance (toe-off). A neutral stance aligns the foot with the body’s center of gravity, minimizing stress on joints. Variations can stem from anatomical factors like arch height, leg length discrepancies, or muscle imbalances, often leading to compensatory gait patterns. Proper stance ensures efficient energy transfer, reducing fatigue and preventing issues like shin splints or knee strain

Pro Tips : Observe stance from behind during barefoot walking on a firm surface. Look for symmetry—uneven heel wear or knee valgus/varus signals the need for orthotics or gait retraining.

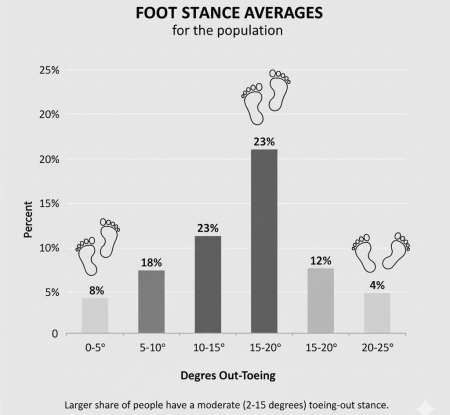

Foot Stance Averages

Average foot stance metrics provide benchmarks for assessing normal vs. abnormal gait. In the Indian population, studies conducted in regions like Karnataka and Tamilnadu show that the foot progression angle (FPA) averages around 2.8° out-toeing in young children (aged 4-5 years), increasing with age to 7.3° by age 16. This indicates that a moderate toeing out stance (typically 2-15 degrees) is common among the largest share of the population, becoming more prevalent in adolescents, adults, and especially the elderly, with higher incidence among males.

Globally, the FPA typically ranges from 5° to 18° of abduction (slight out-toeing) in healthy adults, with a mean of about 7°-10°. In standing, the average angle between feet is around 26° for both left and right in some studies, reflecting a natural V-shape for stability. Population comparisons show variations: children often exhibit in-toeing (negative FPA) that resolves by age 7-8, while older adults may trend toward out-toeing due to hip external rotation. In flat-arched individuals, stances may widen for better support, increasing FPA by 5°-10° compared to high-arched feet. Gender differences are minimal, but males average slightly lower hallux angles (10.8°) vs. females (12.7°). These averages highlight the need for personalized shoe fitting to accommodate deviations.

Foot Stances in Walking

In walking, foot stance influences stride length, stability, and energy expenditure. Here’s a breakdown:

a. Excessive Toeing Out (Duck-Footed): Feet angle outward excessively (FPA >15°-20°). Caused by external tibial torsion or hip retroversion, it widens the base of support for stability but increases lateral foot stress and hip strain. This can lead to plantar fasciitis or IT band issues, as it alters the weight path outward.

b. Toe Straight Ahead: Feet align parallel to the walking direction (FPA near 0°). This neutral stance optimizes propulsion, distributing weight evenly across the foot and minimizing lateral stresses. It’s ideal for efficiency but rare; most people have slight variations. Benefits include reduced knee torque and better balance, though it may feel unnatural if not habitual.

c. Toeing In (Pigeon-Toed): Feet point inward (negative FPA, e.g., -5° to -15°). Common in children due to femoral anteversion or tibial torsion, it shortens functional foot length, accelerating forward momentum but increasing tripping risk. In adults, it can cause medial knee pain or bunions from uneven pressure. Often resolves naturally, but persistent cases may need orthotics.

Pro Tip: Train neutral alignment with mirror feedback or tactile cues (e.g., tape on the floor). Strengthen hip external rotators for out-toeing; stretch adductors for in-toeing. Reassess every 3 months.

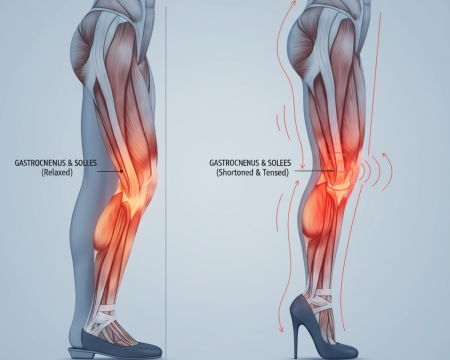

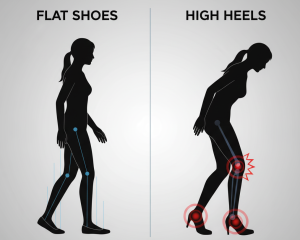

Calf Muscles Showing Flat and High Heel

High heels alter calf muscle biomechanics by forcing the ankle into plantarflexion, shortening the gastrocnemius and soleus muscles. In flat shoes, calves maintain natural length, allowing full dorsiflexion and efficient push-off. High heels reduce muscle length by 10-20%, increasing stiffness and Achilles tendon strain over time. This can lead to reduced flexibility, pain, and altered gait, with more knee flexion to compensate.

Pro Tip : Limit high heels to <2 hours daily. Counteract shortening with daily calf stretches (hold 30s x 3) and eccentric heel drops on a step to rebuild Achilles resilience.

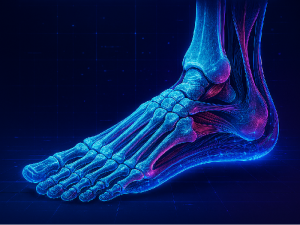

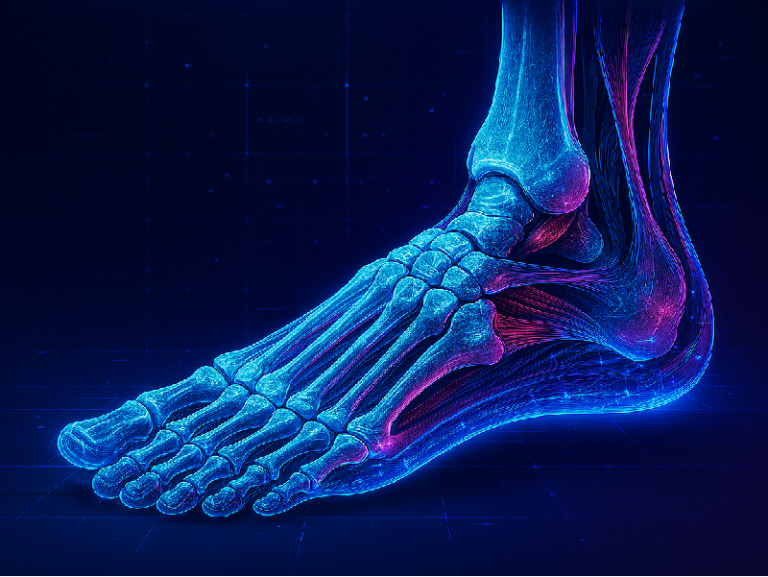

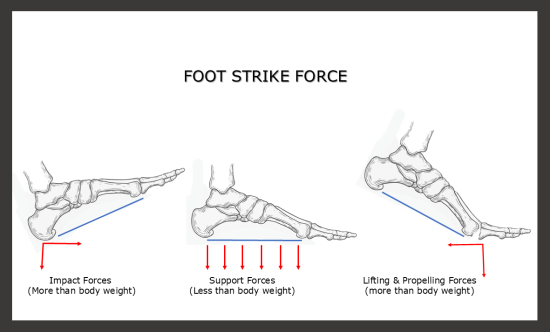

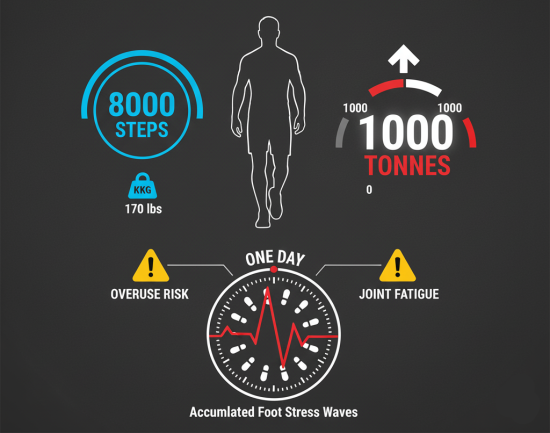

Foot Stress Pressure, Cumulative Daily Foot Stress

Foot stress pressure refers to the distribution of forces across the plantar surface during walking. Pressure peaks at heel strike (up to 1.5x body weight), shifts to midfoot for support, and concentrates at the forefoot (metatarsal heads) during propulsion. Regions include: heel (initial impact), lateral midfoot (stability), central forefoot (main load), and toes (final push). In older adults, pressure increases at metatarsals due to reduced fat padding. Uneven distribution can lead to ulcers or fractures; insoles help redistribute.

For a 170-pound (77 kg) man taking 8000 steps daily, the cumulative force on the feet approximates 1000 metric tonnes, factoring in ground reaction forces of 1.5-1.6x body weight per step. This accounts for ~4000 strikes per foot, with total load summing peaks and impulses—equivalent to lifting a small car repeatedly. Such stress underscores the need for supportive shoes to mitigate fatigue and injury.

Pro Tip: Rotate shoes daily to allow midsole recovery (48–72 hours). Track steps via app—if exceeding 10,000 regularly, upgrade to zero-drop or maximalist cushioning to offset cumulative impact.

High Heels: Postural Alterations and Risks

Contrast this with high heels, which disrupt biomechanics profoundly. The forward tilt demands compensatory knee bend and pelvic tuck, shortening the Achilles and overloading the forefoot. Chronic wear risks bunions, plantar fasciitis, and spinal strain—altering the gait cycle’s elegant flow into an unstable teeter.

The Running Foot: Enhanced Stresses and Adaptations

Transitioning from walking, the running foot—or more aptly, the “athletic foot”—endures exponentially greater loads. Since the 1970s fitness boom, gait labs have revolutionized our understanding, fueling innovations in athletic shoe design. Running amplifies traumatic forces: impacts multiply by 2-3 times body weight, and styles vary—heel strikers land posteriorly for endurance, forefoot strikers anteriorly for speed, while midfoot styles (common in sprinters) distribute evenly.

Athletes in tennis, basketball, or soccer face even wilder extremes: a 200-pound player landing from a three-foot jump generates nearly two tons of force per foot. This invites “toe trauma” (turf toe in football, tennis toe in racquet sports), where momentum jams digits against the shoe’s toe box, causing swelling and fractures. Achilles strains and arch pulls compound the risk, underscoring the need for adaptive footwear.

Pro Tip: Match shoe drop (heel-to-toe offset) to strike pattern: 8–12mm for heel strikers, 4–6mm for midfoot, 0mm for forefoot. Test with slow-motion video analysis.

Styles of Running and Foot Impact

Runner profiles dictate strike patterns:

- Sprinters: Explosive forefoot focus, smaller contact area, higher peak stresses.

- Distance Runners: Broader midfoot engagement, sustained loads for efficiency.

- Court Athletes: Lateral twists and stops add shear forces, demanding multi-directional traction.

Shoe evolution reflects this: modern designs shed half their weight (now ~6-8 ounces), reducing “footlift load” that taxes oxygen and drags performance. Over a five-mile run, a six-ounce savings equates to less muscular drag and fatigue.

Pro Tip: Every 100g reduction in shoe weight saves ~1% energy over distance. Prioritize lightweight mesh uppers and carbon plates for competitive runners.

Endurance and Injury Prevention

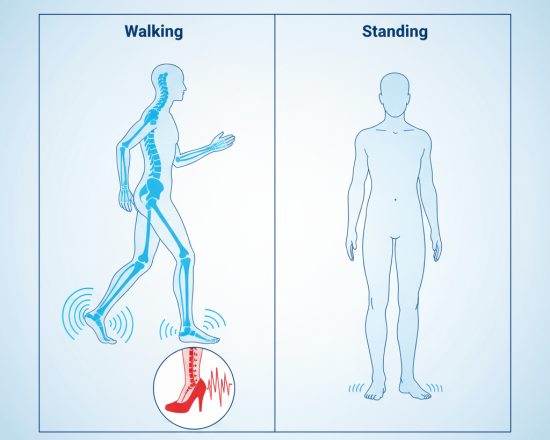

TRunning’s rigors heighten demands on muscles, nerves, and circulation—maximizing stretch, blood flow, and neural firing for propulsion. Yet, without adaptation, injuries loom: repetitive heel strikes send “tremor waves” up the kinetic chain, potentially jarring the spine over a lifetime (200 billion impacts for avid walkers). Prevention starts with specialized shoes: orthotic inserts for arch support, shock-absorbing midsoles, selective lacing for secure fit, and traction outsoles to grip varied surfaces.

Lightweight uppers in soft leather flex with the foot, while round-toe boxes prevent toe bunching. For court sports, low-cut designs enhance agility without sacrificing stability.

Pro Tip: Follow the 10% rule—increase weekly mileage by no more than 10%. Incorporate strength sessions (single-leg squats, calf raises) twice weekly to bulletproof tendons

Athletic Shoes: Design for Performance and Comfort

Athletic footwear is engineered for the foot’s extremes. Cushioning midsoles (EVA foam, gel inserts) attenuate step shock, while breathable meshes manage heat. Weight optimization cuts oxygen debt, and ergonomic lasts mimic the foot’s dynamic curve. Precision fit—via adjustable laces and removable insoles—ensures no slippage during high-impact pivots.

Pro Tip: Replace shoes every 400–500 miles. Check midsole compression—fold the shoe; if it creases deeply, cushioning is compromised.

Step Shock and Cushioning Needs

Each heel strike unleashes “step shock”—vibrational tremors that ripple through the body column, more taxing than static standing due to cumulative muscular demands. Walking counters this with a “pumping” action: leg muscles act as a second heart, boosting circulation and oxygenation. This is why walking trumps standing for endurance—we tire faster idle than in motion, as strides enhance venous return and respiratory depth.

Cushioned soles and heels mitigate shocks, while flat or low-heel profiles preserve natural alignment, reducing forefoot burden.

Pro Tip: Choose shoes with 20–30mm stack height and responsive foam (e.g., PEBA) for shock absorption without sacrificing ground feel. Test bounce—drop from 10cm; it should rebound >50%.

Physiological Benefits of Walking

Beyond mechanics, walking’s rhythmic cadence invigorates health: deeper breaths oxygenate tissues, stimulated circulation flushes toxins, and moderate loads build resilience without overload. It’s the ultimate accessible exercise—gentle yet profound, easing into daily life with shoes that amplify, not impede, these gains. Opt for lightweight, round-toed walkers with soft uppers and precise fit to unlock full comfort.

Pro Tip: Walk 30 minutes daily at brisk pace (100–120 steps/min). Add intervals (1 min fast, 2 min moderate) to boost VO₂ max and calorie burn by 20%.

Conclusion

From the heel’s initial kiss with the ground to the toes’ final grip, the biomechanics of the walking foot—and its running counterpart—reveal a system engineered for resilience and grace. Integrating anatomy (tarsus stability, metatarsus spring, phalange grip) with dynamics (stress paths, shock absorption, propulsion) demands footwear that evolves with motion, not against it. As we’ve traced from foundational support to athletic extremes, the message is clear: static measurements fall short. Professional fitting must embrace the dynamic foot—loaded, flexed, and alive—prioritizing cushioning, lightweight design, and ergonomic alignment to prevent injuries, boost endurance, and elevate performance.

In a world of sedentary traps, reclaim your stride: choose shoes that honor your foot’s biomechanical ballet. Whether pounding pavement or leaping courts, the right fit turns every step into empowered progress. What’s your go-to for gait optimization? Share in the comments—let’s stride forward together.